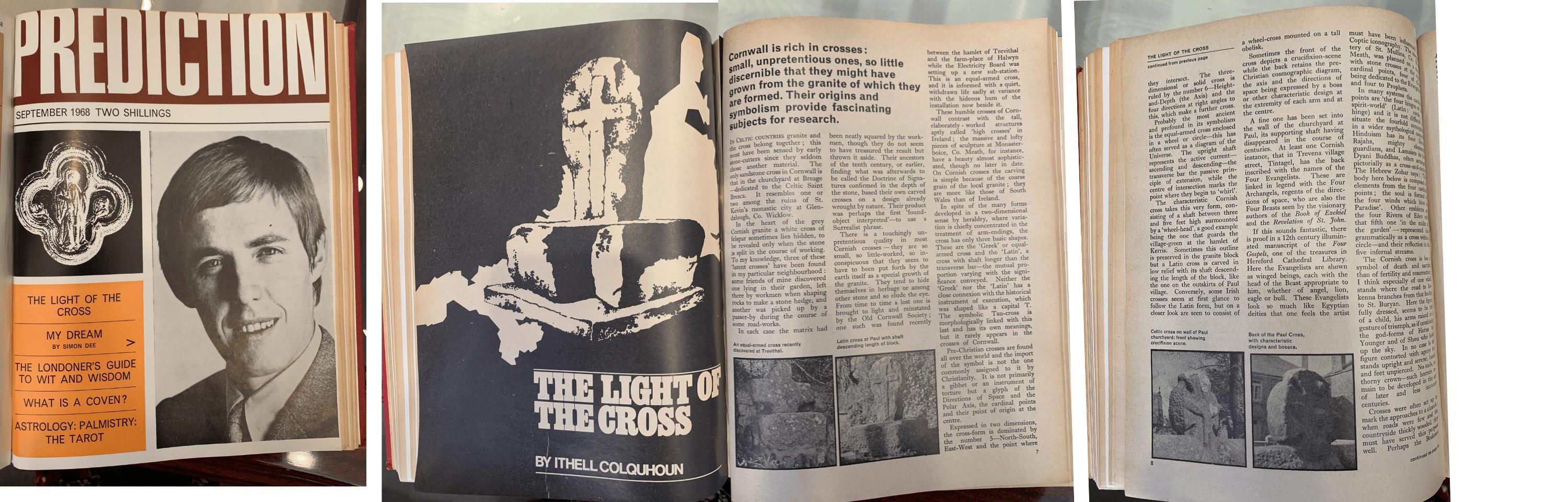

Within The College of Psychic Studies is an extensive library archive of historical esoteric magazines. This collection includes a catalogue of Prediction. Established in 1936, Prediction was the UK's longest-running spiritual publication. Here is an article written by artist Ithell Colquhoun (1906-1988) and published in the September 1968 issue of Prediction.

The Light of the Cross, by Ithell Colquhoun

Cornwall is rich in crosses: small, unpretentious ones, so little discernible that they might have grown from the granite of which they are formed. Their origins and symbolism provide fascinating subjects for research.

In Celtic countries granite and the cross belong together; this must have been sensed by early stone-cutters since they seldom chose another material. The only sandstone cross in Cornwall is that in the churchyard at Breage - dedicated to the Celtic Saint Breaca. It resembles one or two among the ruins of St Kevin's monastic city at Glendalough, Co. Wicklow.

The heart of the Cornish cross

In the heart of the grey Cornish granite a white cross of felspar sometimes lies hidden, to be revealed only when the stone is split in the course of working. To my knowledge, three of these 'latent crosses' have been found in my particular neighbourhood: some friends of mine discovered one lying in their garden, left there by workmen when shaping rocks to make a stone hedge, and another was picked up by a passer-by during the course of some road-works.

In each case the matrix had been neatly squared by the workmen, though they do not seem to have treasured the result but thrown it aside. Their ancestors of the tenth century, or earlier, finding what was afterwards to be called the Doctrine of Signatures confirmed in the depth of the stone, based their own carved crosses on a design already wrought by nature. Their product was perhaps the first 'found object interpreted' - to use a Surrealist phrase.

Comparing Cornish crosses with the high cross of Ireland

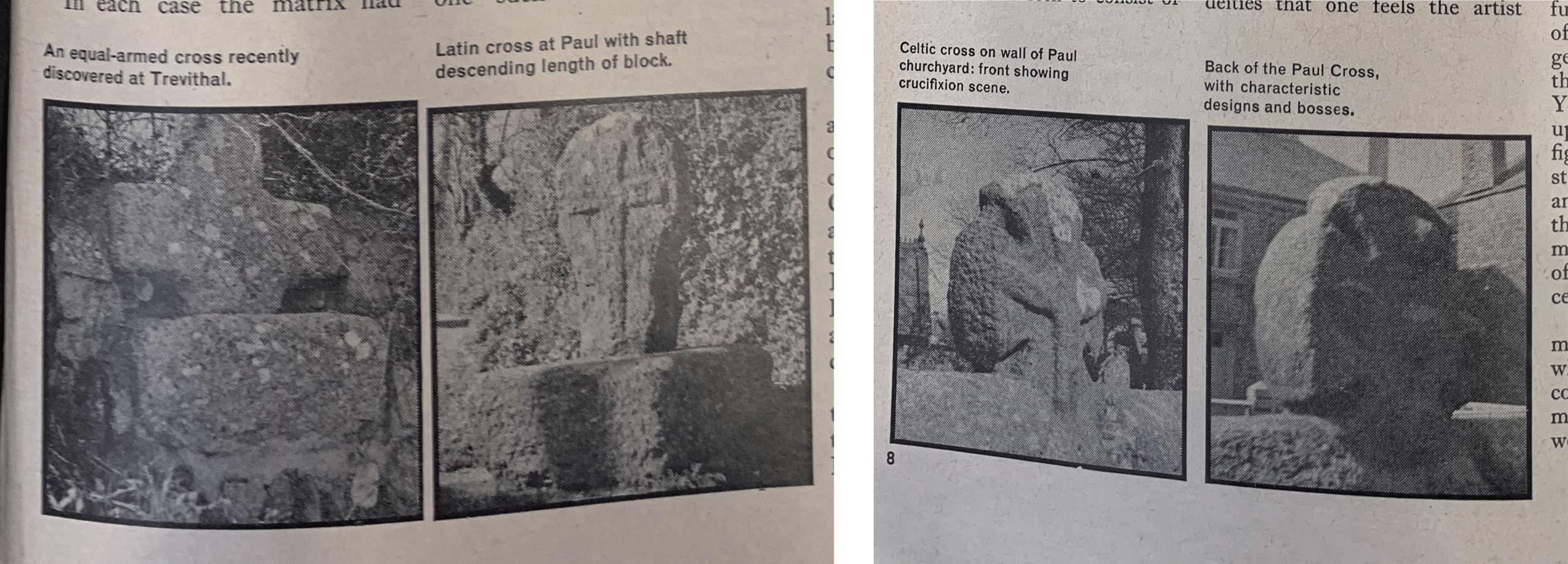

There is a touchingly unpretentious quality in most Cornish crosses - they are so small, so little-worked, so inconspicuous that they seem to have been put forth by the earth itself as a special growth of the granite. They tend to hide themselves in herbage or among other stones and so elude the eye. From time to time a lost one is brought to light and reinstated by the Old Cornwall Society; one such was found recently between the hamlet of Trevithal and the farm-place of Halwyn while the Electricity Board was setting up a new sub-station. This is an equal-armed cross, and it is informed with a quiet, withdrawn life sadly at variance with the hideous hum of the installation now beside it.

These humble crosses of Cornwall contrast with the tall, elaborately-worked structures aptly called 'high crosses' in Ireland; the massive and lofty pieces of sculpture at Monasterboice, Co. Meath [sic.], for instance, have a beauty almost sophisticated, though no later in date. On Cornish crosses the carving is simple because of the course grain of the local granite; they are more like those of South Wales than of Ireland.

Three shapes of stone cross

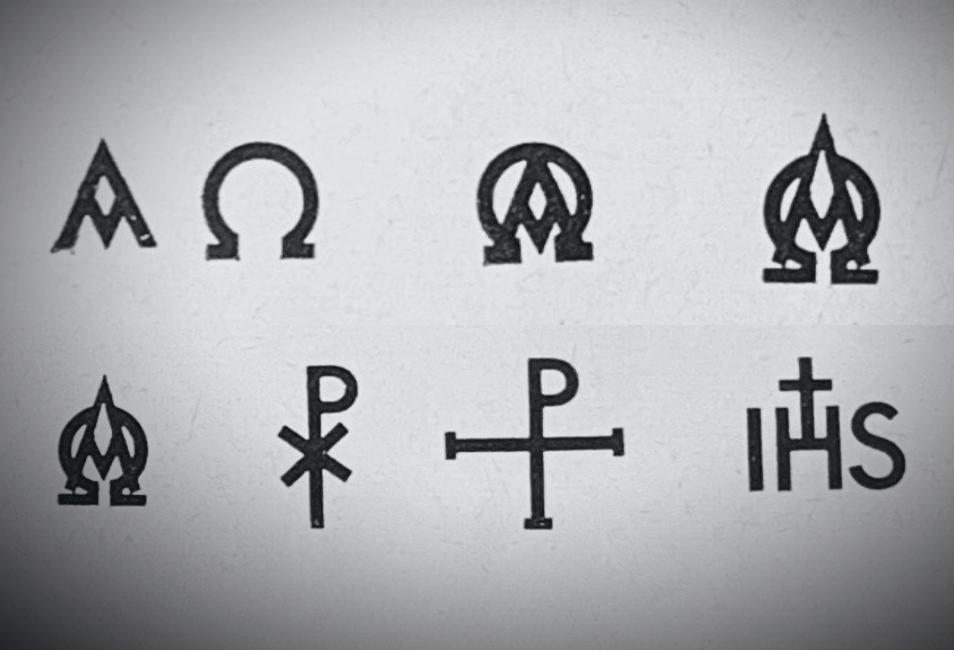

In spite of the many forms developed in a two-dimensional sense by heraldry, where variation is chiefly concentrated in the treatment of arm-endings, the cross has only three basic shapes. These are the 'Greek' or equal-armed cross and the 'Latin', a cross with the shaft longer than the transverse bar - the mutual proportion varying with the significance conveyed. Neither the 'Greek' nor the 'Latin' has a close connexion with the historical instrument of execution, which was shaped like a capital T. The symbolic Tau-cross is morphologically linked with this last and has its own meanings, but it rarely appears in the crosses of Cornwall.

Mystical symbolism of pre-Christian crosses

Pre-Christian crosses are found all over the world and the import of the symbol is not the one commonly assigned to it by Christianity. It is not primarily a gibbet or an instrument of torture but a glyph of the Directions of Space and the Polar Axis, the cardinal points and their point of origin at the centre.

Expressed in two dimensions, the cross-form is dominated by the number 5 - North-South, East-West and the point where they intersect. The three-dimensional or solid cross is ruled by the number 6 - Height-and-Depth (the Axis) and the four directions at right angles to this, which make a further cross.

Probably the most ancient and profound in its symbolism is the equal-armed cross enclosed in a wheel or circle - this has often served as a diagram of the Universe. The upright shaft represents the active current - ascending and descending - the transverse bar the passive principle of extension, while the centre of the intersection marks the point where they begin to 'whirl'.

Cornwall cross characteristics

The characteristic Cornish cross takes this very form, consisting of a shaft between three and five feet high surmounted by a 'wheel-head', a good example being the one that guards the village-green at the hamlet of Kerris. Sometimes this outline is preserved in the granite block but a Latin cross is carved in low relief with its shaft descending the length of the block, like the one on the outskirts of Paul village. Conversely some Irish crosses seem at first glance to follow the Latin form, but on a closer look are seen to consist of a wheel-cross mounted on a tall obelisk.

Sometimes the front of the cross depicts a crucifixion-scene while the back retains the pre-Christian cosmographic diagram, the axis and the directions of space being expressed by a boss or other characteristic design at the extremity of each arm and at the centre.

A fine one has been set into the wall of the churchyard at Paul, its supporting shaft having disappeared in the course of centuries. At least one Cornish instance, that in Trevena village street, Tintagel, has the back inscribed with the name of the Four Evangelists. These are linked in legend with the Four Archangels, regents of the directions of space, who are also the Four Beasts seen by the visionary authors of the Book of Ezekiel and the Revelation of St. John.

The significance of 'four'

If this sounds fantastic, there is proof in a 12th century illuminated manuscript of the Four Gospels, one of the treasures in Hereford Cathedral Library. Here the Evangelists are shown as winged beings, each with the head of the Beast appropriate to him, whether of angel, lion, eagle or bull. These Evangelists look so much like Egyptian deities that one feels the artist must have been influenced by Coptic iconography. The mystery of St Mullins, Co. Carlow, was planned with stone crosses at the eight cardinal points, four of them being dedicated to the Evangelists and four to the Prophets.

In many systems the cardinal points are the 'four hinges of the spirit-world' (Latin: cardo, hinge) and it is not difficult to situate the fourfold conception in a wider mythological context. Hinduism has its four Rajahs, mighty elemental guardians, and Lamaism its five Dyani Buddhas, often arranged pictorially as a cross-and-centre. The Hebrew Zohar says: "The body here below is composed of elements from the four cardinal points; the soul is formed of the four winds which blow in Paradise'. Other emblems are the four Rivers of Eden with that fifth one in the 'midst of the garden' - represented diagrammatically as a cross within a circle - and their reflection in the five infernal streams.

The Cornish cross is less a symbol of death and sacrifice than of fertility and resurrection. I think especially of one which stands where the road to Boskenna branches from that leading to St Buryan. Here the figure, fully dressed, seems to be that of a child, his arms raised in a gesture of triumph, as if combining the god-forms of Horus the Younger and of Shou who holds up the sky. In no case is the figure contorted with agony but stands upright and serene, hands and feet unpierced. No nails or thorny crown - such horrors remain to be developed in the art of later and less innocent centuries.

With gratitude to the artist Ithell Colquhoun and Prediction magazine for this article - as fascinating and relevant today as it must have been back in the summer of 1968. Ithell Colquhoun wrote quite a few features for Prediction. To find out more, please contact The College of Psychic Studies' archivist & curator, Jacqui McIntosh at jacqui@collegeofpsychicstudies.co.uk.

Become a member to support the care of our library & archive:

Join our newsletter to keep in touch with The College of Psychic Studies.